|

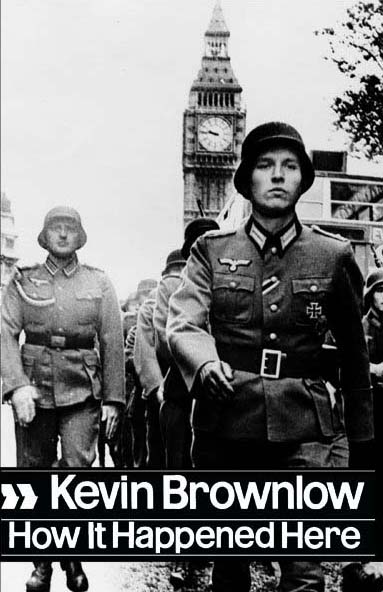

This is the story of the making of a film called It Happened Here. I

know that few of you will have heard of it and there is a reason for

this. The film was the part–time project of two teenage boys back in

the 1960s, and it took them eight years to see it through from its

conception as an idea to the film’s brief national release in 1966.

Because of the controversy it stirred – up it was effectively suppressed

by the entire movie industry, including its own distributor. In order to

have it released at all the two young co-Directors were required to

agree to the cutting of a six-minute sequence that the distributors

United Artists regarded as simply too hot to handle.

The ultimate blue movie? Only in a very special sense. Had it

contained explicit sex scenes its censorship and suppression would

have been far simpler for the guardians of public taste and morals.

This was a film about the epidemiology of Fascism. How the disease

takes hold and how it spreads and what it does to the minds of those

it infects. And in dealing with this subject matter the film-makers

dared to suggest that the British people were no different to any

others, that Fascism is not some alien foreign import but an ever-

present dark undercurrent in human nature itself.

Hitler has taken over from the Devil as the icon of evil in the West,

and this is understandable. The Holocaust truly represented a new

trench dug at the bottom of the cess-pit of human behaviour. It was

the first attempt at the industrialisation of murder. The philosophy of

Henry Ford applied to the task of terminating human life. But the

symbolism of a Devil, a Hitler or an Eichmann is also an effective way

of convincing ourselves that the people who did those things weren’t

the same as us. They were out there somewhere, foreigners, fanatics: the bogey-men and monsters that we fought in history’s one unassailably

Just War – and we won! How often has this assumption of the

‘otherness’ of the Fascist been questioned in art or literature? Hardly

at all I would suggest. The Fascist, the Nazi, is the Villain of the

morality play, his mental processes unfathomable, his evil absolute.

He is simply a cipher to be overcome by the people we identify with,

the ones who represent ourselves.

Leonard Cohen called this view into question in his poem All There Is

to Know about Adolf Eichmann. First he tells us how ordinary

Eichmann was: average height, average weight, average intelligence,

no distinguishing marks. Then he hits us with the killer final stanza:

What did you expect? Talons? Oversize incisors? Green saliva?

Madness?

Kevin Brownlow and co–Director Andrew Mollo took this a stage

further and tried to show us exactly how the ordinary person of

average everything turns into the nurse administering the lethal

injections in the genteel rural euthanasia mill. This is shown to be a

process not so much of intellectual conversion as of resignation and

conformity to the role that society allocates. The film confronts each

viewer with the question: What would I have done? It personalises the

spread of the twentieth century’s most toxic political ideology.

Essentially it holds up a mirror and asks us to look at ourselves, which

is exactly what should be going on when art, particularly narrative art

like film, literature and theatre, is doing its job.

The book describes the evolution of the boys’ thinking as they solved

the seemingly impossible technical problems of creating a feature

film without finance, backing or even very much time, enlisting the

help of friends, acquaintances and kindly strangers, borrowing a

camera (which was almost immediately stolen) and visiting flea

markets to buy old German tunics and Nazi regalia.

The original idea was to tell the story of a hypothetical German invasion of England

following the Dunkirk retreat, leading to a period of occupation and

partisan activity, and ending with the country’s liberation by

American troops in the closing year of the war. A counter-factual war

adventure, with lots of battle scenes and heroics. But as the boys

learned more about Fascism, met committed British Fascists like

Frank Bennett, and began to think about what occupation really

meant, the film departed from its Boys’ Own beginnings to become

something far darker and more significant: a portrait of a Fascist

England that might have been, presented with a narrative distance

that was later to be mistaken by some for approval.

This is a many-layered book, partly the personal testament of a filmmaker who believes that his work has been misunderstood, partly a

technical notebook about how (and how not) to make a film, partly a

glimpse inside the power-politics of the film industry, partly an

account of the actual events surrounding the film’s release and the

reactions of press, actors’ unions, early audiences and the Board of

Deputies of British Jews.

Most of all though it is an account of what it

is that drives an artist to create and the constraints that operate

even in the most liberal of Western democracies on what the artist is

allowed to say. It’s also inhabited throughout by the dry wit and stoic

humour of the author, and if all that isn’t enough it contains more

than one hundred photographs, mostly (though not all) stills from the

superb, chilling film they eventually created.

Even if you aren’t particularly a film buff or student of twentieth

century politics, indeed even if you can only afford to buy one book

this year, I recommend without qualification that you should make that one book How It Happened Here.

The film itself is available on DVD and Video from MovieMail and of course Amazon.

SEND ME AN EMAIL

|