|

Back to First Page

Harpsichord

By David Gardiner

This story may be reproduced in whole or in part for any non-commercial purpose provided that authorship is acknowledged and credited.

The copyright remains the property of the author

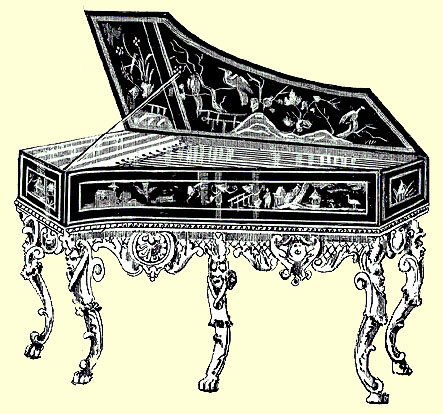

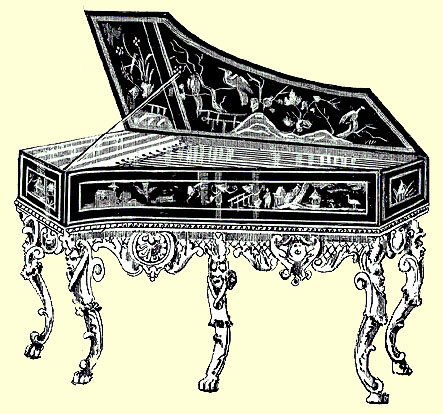

“We have exceptionally good provenance for this instrument,” the auctioneer explained in his measured, slightly superior Oxford accent, “We know that it was made by Julião Antunes for the royal chapel of Lisbon in the year 1749, and presented to the Scarlatti family in Madrid by King Joseph I of Portugal in 1756. It was the actual instrument on which Domenico Scarlatti composed the majority of his sonatas. The instrument was also played by Dominico’s younger brother Pietro Filippo, and remained in the Scarlatti family until the outbreak of the First World War. If I might venture a personal opinion, I believe this to be the finest instrument of its kind that has come onto the market in my twenty-eight years in this profession. It has been meticulously maintained and is in tune and fully playable, as Dr. Saul Lander, Professor of Harpsichord at Trinity College of Music, has kindly agreed to demonstrate.”

The tall slender professor approached the instrument as one might an emperor on his throne: slowly, respectfully, humbly. He seated himself at the stool, stroked back his unruly silver-grey hair with his left hand, and glanced at the classical landscape painted on the underside of the open lid before he began. When the voice of the instrument was heard it was mellow, understated, compelling. He played the beginning of a Scarlatti sonata in C major. The room seemed to hold its breath, the instrument responded as though it knew the notes itself. A charmed few minutes passed. Lander found himself choking up with an emotion to which he could put no name. He scolded himself for his lack of professionalism. Unable to finish the piece, he chose a suitable point at which to pause and allow himself to recover.

A single individual in the silent audience began to applaud. Others joined in. In seconds the room had turned from an auction room to a concert hall, acknowledging the genius of the composer, the instrument maker and the performer. Lander stood up, offered a shallow bow to the audience, and returned to his seat, shaken.

When the applause died down the auctioneer resumed his measured speech as though this glimpse of the divine had not happened. “I have a reserve on this item,” he announced coldly, “and will therefore suggest that we start the bidding at two-hundred and twenty thousand. Do I see that in the room? Thank you. Do I see two hundred and thirty? Thank you, Sir. Against you at the back, Madam…” His voice droned on. Lander did not listen. There seemed something obscene about putting an instrument like that up for sale. An instrument that contained the soul of its maker, that for almost three hundred years had inspired composers and musicians to push forward the limits of human accomplishment. It had been made for a church, reverently and lovingly, by the foremost craftsman of his generation; now it was a commodity, like a sack of potatoes, to be auctioned off to the highest bidder.

Lander considered walking out, but he knew that doing so would attract too much attention – that it would be interpreted as just what it was, an expression of contempt for those who put a monetary value on the likes of this. He sat tight and tried to lose himself in his thoughts. It would soon be over, and with luck the item might go to somewhere where its life could continue: a college or conservatory where new generations of talented musicians could hear what the harpsichord had to teach them and become better musicians and better human beings by their contact with its magic.

At last the hammer fell and Lander’s discomfort seemed set to end. He noted that the sale had gone to the young blonde woman seated near him at the front – rather tartily dressed, he thought, bright colours, high heels, low neckline – not at all the kind of person a conservatory would send along as an agent. More like a refugee from one of those adolescent girl bands, or a reporter from a fashion magazine. Her appearance did not augur well for the instrument, he thought.

The business of the auction had paused now, the young woman got up to go to the office and sign the documents of sale. Lander stood up also, and to his surprise a murmur of applause rippled once again through the audience. He turned and smiled, gave them an embarrassed nod, and continued on his way behind the woman.

In the antechamber the young woman turned towards him and smiled broadly. “Professor Lander, I like very much your playing the Scarlatti tune.” She had a strong accent, Spanish or Italian.

“Thank you, Madam,” he replied, hoping that he didn’t sound as hostile as he felt, “Scarlatti wrote pretty good tunes.” The sarcasm slipped out despite his efforts to be civil. Its sharpness seemed to be lost on the woman, possibly because she wasn’t a native English speaker.

“I think so too. My husband played Scarletti tunes when he was student in Madrid. That why I buy the instrument. He has more time now, maybe he play again.”

Lander was becoming angrier but he did not want to let it show. “Indeed. I hope that his ownership of the instrument may pave the way for a rewarding hobby.”

“I think maybe I need to explain you, Professor Lander. Maybe we sit down, yes?”

Clearly some of Lander’s feelings had communicated themselves to the woman. He had no strong desire to listen to her story but felt that courtesy demanded he should. They sat down together at a fine mahogany table and were immediately approached by one of the auction house attendants. “Would you care for a drink, Madam, Sir?” he enquired respectfully.

“I would love gin and tonic,” the woman replied with enthusiasm.

“Coffee please,” Lander said quietly, “milk, no sugar.” The man hurried off to do their bidding.

“You mind I smoke?” the woman asked as she produced a packet from her shoulder bag. Lander intensely disliked the habit but assured her that he did not. As she lit up, another attendant appeared, seemingly from nowhere, and placed an ashtray on the table. There was really nothing at all that Lander liked about this woman.

Lander thought of his own institution and his own students. Struggling, dedicated young musicians who worked night shifts to pay their fees, who would sell their souls for the chance to play for ten minutes on an instrument of that quality. “Forgive me, Madam, but I am curious. Am I to understand that you have just paid almost half a million pounds for that instrument as a gift for your husband who is an amateur musician? Is this the kind of thing that you do often?”

“No, I just do it this once. Don’t worry Professor Lander. My husband have big house now, servants, he look after the instrument. Maybe our children they play it too. He make money in the computer industry, but not what my husband want to do. My husband soul is musician soul. I know this. He want this instrument for long, long time. Maybe some day you come to our house in Spain and play this instrument too, yes?”

“That would be… a great privilege. May I know your name?”

“Sure. Here, I give you my card. We live outside Madrid. You come see us any time. Any time at all.”

Lander took the card. He was expecting to see a picture of a computer or something modern and technical but instead it bore a small family crest in blue and red, above the gold embossed name and address. The name on the card was Maria Magdalena Scarlatti.

SEND ME AN EMAIL

|